Boggle Revisited: Finding the Globally-Optimal 3x4 Boggle Board

Over 15 years ago (!) I wrote a series of blog posts about the board game Boggle. Boggle is a word search game created by Hasbro. The goal is to find as many words as possible on a 4x4 grid. You may connect letters in any direction (including diagonals) but you may not use the same letter twice in a word (unless that letter appears twice on the board).

You score points for each word you find, with longer words being worth more points (3-4 letters are 1 point, 5=2 points, 6=3 points, 7=5 points, 8+ letters=11 points).

Boggle is a fun game, but it’s also a fun Computer Science problem. There are three increasingly hard problems to solve as you go down this rabbit hole:

- Write a program to find all the words on a Boggle board. This is a classic data structures and algorithms problem, and sometimes even an interview question. What’s wonderful about this problem is that it’s a perfect use for a Trie (aka Prefix Tree), and a counter to the idea that hash tables are always the best answer. You can find many, many Boggle solvers of this sort on the internet. Apparently Jeff Dean is a fan of Boggle, and LLMs can even write these sorts of solvers.

- Find high scoring Boggle boards. Once you’ve written a fast solver, a natural question is “what’s the Boggle board with the most points on it?” The usual approach is some variation on simulated annealing or hill climbing. Start with a random board and find all the words on it. Then change a letter or swap two letters and see if it improves things. Repeat until you stall out. This problem is less popular than the first, but you can still find a few about it and a Code Golf competition. There’s even a published article from 1982 about it! (Fun fact: they found the wrong board.)

- Prove that a Boggle board is the global optimum. If you do enough simulated annealing runs, you’ll see the same few boards pop up again and again. A natural next question is “are these truly the highest-scoring boards?” Are there any high-scoring boards that simulated annealing misses? Proving a global optimum is much harder than finding a few high-scoring boards and, so far as I’m aware, I’m the only person who’s ever spent significant time on this particular problem.

The crowning achievement of my work in 2009 was proving that this was the highest-scoring 3x3 Boggle board (using the ENABLE2K word list), with 545 points:

R T S

E A E

P L D

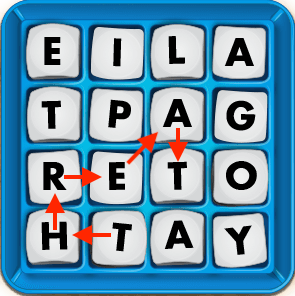

Now, 15 years later, I’ve been able to prove that this is the best 3x4 board, with 1651 points:

S L P

I A E

N T R

D E S

This post will summarize how I found the highest-scoring 3x3 Boggle board back in 2009, and the next will describe how I extended this to 3x4 in 2025. Alas, 4x4 Boggle still remains out of reach for now. Maybe in 2040?

Why is this a hard/interesting problem?

There are an enormous number of possible Boggle boards. Something like 26^16/8, which is around 5 billion trillion (5*10^21). This is far, far too many to check one by one. I previously estimated that it would take around 2 billion years on a single CPU.

And yet… there’s a lot of structure in this problem that might be exploited to make it tractable. There’s an enormous number of possible optimizations to try, lots of interesting data structures and algorithms to read about and implement, and always the possibility that you’re one insight away from solving this problem.

Boggle is a worthy adversary, and most ideas don’t pan out. But the possibility of achieving such an enormous speedup (2 billion years → a few hours) is what makes this problem exciting to me.

Why pick it back up now?

Fifteen years is a long time! The world has changed a lot since my last Boggle post. Computers have gotten much faster. There have been five new versions of C++. Cloud computing is a thing now. Stack Overflow is a thing. So are LLMs. A cool language called TypeScript came out and I wrote a book on it. I even have an iPhone now!

I’ve gotten in the habit of doing the Advent of Code, a coding competition that’s held every December. It involves lots of data structures and algorithms problems, so it got me in that headspace.

In addition, I’ve long been curious to write code using a mix of C++ and Python: C++ for the performance-critical parts, Python for everything else. Maybe it could be a best-of-both worlds: the speed of C++ with the convenience of Python. I thought Boggle would be a great problem to use as motivation. I wound up using pybind11 and I’m a fan. I’ll have some thoughts to share about it in a future post.

How did I find the optimal 3x3 board in 2009?

Though I didn’t know it at the time, I used branch and bound, a ubiquitous optimization strategy first developed in the 1960s. There were three key ideas.

Board classes

The first idea was to reduce the number of boards by considering whole classes of boards at once. Here’s an example of a class of 3x3 boards:

| l, n, r, s, y | c, h, k, m, p, t | l, n, r, s, y |

| a, e, i, o, u | a, e, i, o, u | a, e, i, o, u |

| c, h, k, m, p, t | l, n, r, s, y | b, d, f, g, j, v, w, x, z |

I’ve divided the alphabet up into four different “buckets.” Instead of having a single letter on each cell, this board has 5-9 possible letters from one of those buckets on each cell. There are 5,062,500 individual boards in this class. The highest-scoring 3x3 board (rts/eae/pld) is one of them, but there are many others.

There are vastly fewer board classes than individual boards. For 3x3 Boggle, using four “buckets” of letters takes us from 26^9/8 = 6x10^11 boards → 4^9/8 = 32,768 board classes. If we can find the highest-scoring board in each class in a reasonable amount of time, this will make the problem of finding the global optimum tractable.

Bound: Upper bounds on board classes

The second insight is that, rather than finding the highest-scoring board in a class, all we really need to do is establish an upper bound on its score. An upper bound is a concept from mathematics: if the highest-scoring board in a class has 500 points, then 500 is an upper bound on the score. So is 600. The upper bound doesn’t need to be achieved by any particular board, it just needs to be greater or equal to the score of every board.

If the upper bound is less than 545 (the score of the best individual board we found through simulated annealing), then we know there’s no specific board in this class that beats our best board, and we can toss it out without having to score every single board in the class.

As it turns out, establishing an upper bound is much, much easier than finding the best board in a class. I came up with two upper bounds back in 2009:

- sum/union: the sum of the points for every word that can be found on any board in the class.

- max/no-mark: a bound that takes into account that you have to choose one letter for each cell.

You can read more about how these work in the linked blog posts from 2009. The max/no-mark bound is typically much lower than the sum/union bound, but not always. Usually neither of the upper bounds is low enough. On this board class, for example, the sum/union bound is 106,383 and the max/nomark bound is 9,359. Those are both much, much larger than 545!

Branch: Repeatedly split board classes

This brings us to the final insight: if the upper bound is too high, you can split up one of the cells to make several smaller classes. For example, if you split up the middle cell in the board class from above, then this single class becomes five classes, one for each choice of vowel in the middle:

|

|

... |

|

These are the bounds you get on those five board classes:

| Middle Letter | Max/No Mark | Sum/Union |

|---|---|---|

| A | 6,034 | 55,146 |

| E | 6,979 | 69,536 |

| I | 6,155 | 58,139 |

| O | 5,487 | 48,315 |

| U | 4,424 | 37,371 |

Those numbers are all still too high (we want them to get below 545), but they have come down considerably. Choosing “U” for the middle cell brings the bound down the most, while choosing “E” brings it down the least.

Branch and Bound

If we keep splitting up cells, we’ll keep getting more board classes with lower bounds. I didn’t know it in 2009, but this is branch and bound, a ubiquitous approch for solving optimization problems:

- Branch: Split up a cell to get smaller board classes (subproblems).

- Bound: Calculate an upper bound on the board class.

If you iteratively break cells, your bounds will keep going down. If they drop below 545, you can stop. These recursive breaks form a sort of tree. The branches of the tree with lower scores (like the “U”) will require fewer subsequent breaks and will be shallower than the higher-scoring branches (the “E”). The sum/union bound converges on the true score, so if you break all 9 cells and still have more than 545 points, you’ve found a global optimum.

Back in 2009, I reported that I checked all the 3x3 boards this way in around 6 hours. The board you find via simulated annealing is, in fact, the global optimum. In 2025, I’m able to run the same code on a single core on my laptop in around 40 minutes.

This is something like a 400x speedup vs. scoring all the 3x3 boards individually.

How much harder are 3x4 and 4x4 Boggle?

As you increase the size of the board, the maximization problem gets harder for two reasons:

- There are exponentially more boards (and board classes) to consider.

- Each board (and board class) has more words and more points on it.

How bad is this?

- 3x3: each class takes ~80ms to break and there a ~33,000 of them ⇒ ~40 minutes.

- 3x4: each class takes ~1.6s to break and there are ~6.7M of them ⇒ ~78 days.

- 4x4: each class takes ~10m to break and there are ~537M of them ⇒ ~10,000 years.

So with the current algorithms, 3x4 Boggle is ~3,000x harder than 3x3 Boggle and 4x4 Boggle is around 50,000 times harder than that.

That’s enough for today. In the next post, I’ll present a few optimizations on the 2009 approach that net us another ~10x speedup. Enough that it’s reasonable to solve 3x4 Boggle on a single beefy cloud machine, but not enough to bring 4x4 Boggle within reach.

Please leave comments! It's what makes writing worthwhile.

comments powered by Disqus